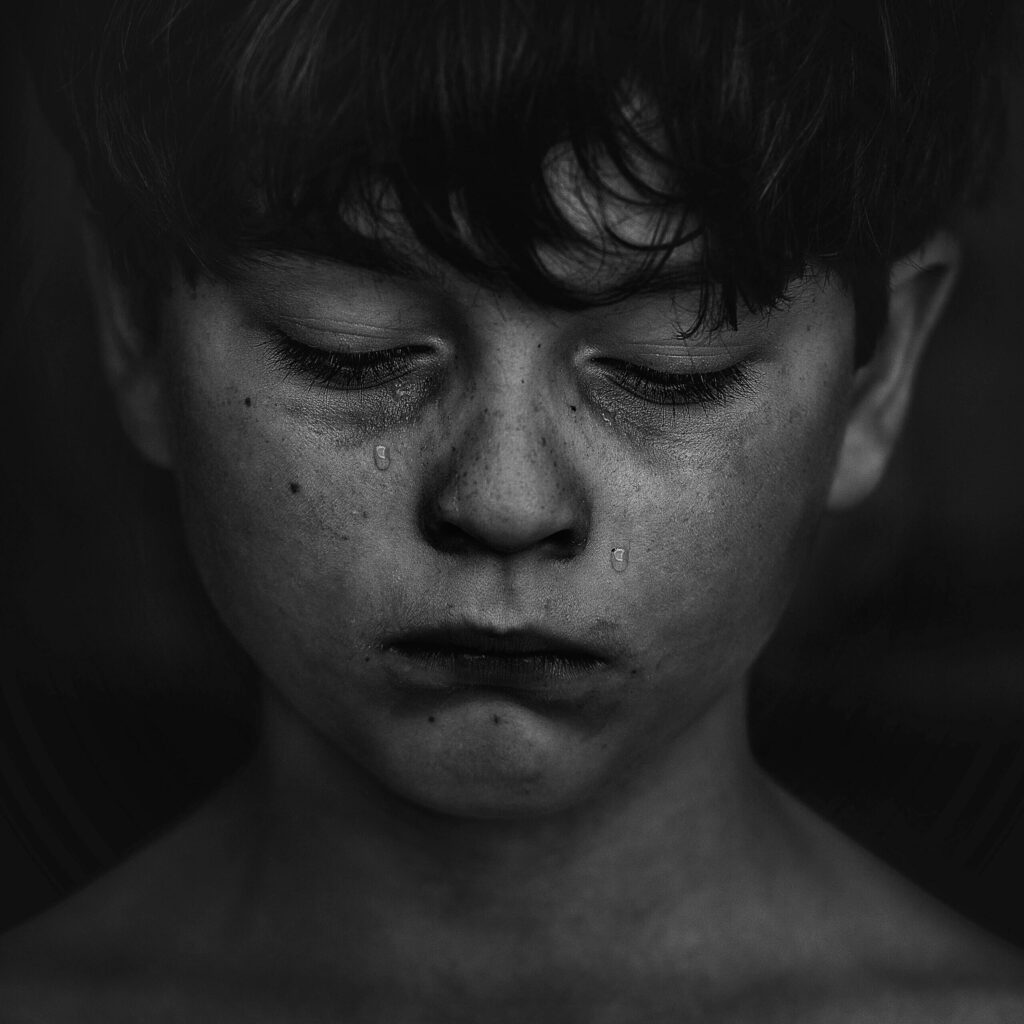

Childhood Trauma Part 1 – 101 on Trauma

How people respond to traumatic events in their lives depends on numerous factors, one of them being the age at which they experience a traumatic event. In very young children, trauma can have a significant impact on their development across all areas of their lives. Some of the ways in which trauma might disrupt a child’s life include (but are not limited to) developmental delays, sensory integration issues, dysregulated behavior and emotions, and difficulty creating meaningful relationships with others.

But let’s dig a little deeper into how trauma affects children, as well as the treatment options that are available to help minimize trauma’s impact on children.

What is trauma?

Trauma is a term that has been thrown around a great deal on social media lately. Simply put, trauma can be the result of an incident that threatens the safety of an individual. Sometimes traumatic symptoms can occur from a single incident, but many individuals seeking therapy have experienced multiple incidents or long-term trauma, also referred to as complex trauma.

ACES (Adverse Childhood Experiences) are potentially traumatic situations that have occurred in childhood, such as: abuse of all kinds, violence in the home, witnessing violence in one’s community, having a parent(s) who is mentally ill and/or addicted to substances, growing up in poverty, parental abandonment and having a parent who was incarcerated.

Community discrimination and generational trauma, as well as bullying, separation from a primary caregiver and medical trauma were left out of the original list of ACES but can also have profound effects on a child’s wellbeing.

Preverbal trauma occurs before the child is old enough to speak or speak fluently (~ages 0-3), which is also before a child is able to create coherent, long-term memories of events. Oftentimes, people struggle to recall many details of traumatic events they experienced during their pre-verbal years. They may even have no memory of it whatsoever. Nonetheless, children and adults can still suffer negative effects of trauma that occurred during their preverbal years.

PTSD-Post Traumatic Stress Disorder is a mental health condition consisting of a constellation of symptoms that occur in some people who have experienced traumatic incidents. Not everyone who has experienced traumatic incidents develops PTSD. Moreover, some people who do not develop PTSD following trauma may instead develop other mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, disordered eating, and substance use disorders.

A Very Short Primer on Attachment

Damage to the relationship between the child and their primary caregiver can also occur in response to trauma. Conversely, damage to the child-caregiver relationship can be traumatic. Secure attachment between child and primary caregiver allows a child to feel safe. Secure attachment forms when a child’s basic needs are met, such as food and shelter, touch, and sensitive emotional interactions from an in-tune primary caregiver that allow the child to feel valued, loved, and safe.

In early childhood, children need a trusted caregiver to help them regulate their emotions. Consider when a baby cries and is picked up and held, for example. The child learns that their emotional needs will be met and, in turn, is more likely to grow up trusting that others will be able and willing to meet their social and emotional needs as well.

When the attachment is not secure, dysregulation of emotions may occur—explosive episodes such as mentioned above are an example of what can happen when a child is dysregulated. And the child is much more at risk for mental health issues and substance use problems, and may be unable to nurture healthy relationships.

Sensory Challenges

Deprivation, neglect, and complex trauma in very young children impact brain development directly, and can make it difficult for them to either filter out or accurately recognize sensory input. Holding, rocking, talking, cooing to infants all plays a huge part in developing the part of the brain that integrates sensory experience.

Imagine children with brain deficits for filtering out sensory stimuli being placed in regular classrooms filled with 28 other kids. Noise, lights, activity can cause intense anxiety and they will be prone to lashing out or may curl up in the corner of the room with their hands over their ears.

Those kids who lash out or cringe in the corner may be performing sensory avoiding behaviors.

And, those children who perform sensory seeking behaviors often appear hyperactive. They may be the kids who can’t keep their hands to themselves, who are always fidgeting or talking or flinging pencils. They are seeking sensory stimulation.

“Deep touch, the rhythm of rocking, all play a part in developing the proprioceptive and vestibular systems”, Rooney explains. The vestibular system is the part of the brain that affects balance and understanding where one’s body is in relationship to others and in space. A child with those deficits may seem unusually clumsy—perhaps often bumping up against other kids or banging into things. Damage to the proprioceptive system can cause delays in gross and fine motor skills.

Executive Function

Executive Functioning is an umbrella term that includes a set of tasks that comes from the prefrontal cortex or the rational, command, decision making part of one’s brain. These skills include time management, prioritizing, organizing, delaying gratification, decision making, remembering to do and complete tasks. Complex trauma can also interrupt the development of the pre-frontal cortex.

It is perfectly normal for kids to forget to do homework or to turn it in late (or not at all) from time to time, or to forget their gloves at school. However, frequent forgetfulness and disorganization may be due to a developmental issue that goes beyond what is considered “normal” for that child’s age and stage of development. A middle school kid may struggle to remember when to do homework assignments and this is normal. A 17 year old teen who has a pattern of forgetting homework, losing items, forgets to brush his teeth or to take showers is likely suffering from executive functioning deficits.

School Difficulties and Cognitive Delays

Traumatized kids are often not set up to learn. There are too many barriers that get in the way for traumatized brains to take in new information, to store and organize new material. Trauma can create an imbalance of the parasympathetic nervous system – the part of the brain that helps people calm down after a frightening incident.

Traumatized children live mostly in survival mode where many situations they encounter can potentially continue to re-traumatize them. When the trauma is re-experienced, the brain’s speech and rational decision-making centers can go offline, making it impossible for the child to calm themselves down enough to make good decisions.

For kids and families who have experienced adversities, healing needs to begin by connecting to their bodies’ inherent wisdom which helps them connect to and regulate their emotions. It is key to repair the ability to securely attach to a trusted caregiver as well. Bruce Perry, a psychiatrist who specializes in child-hood trauma and who wrote the powerful book, “The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog” about his experiences working with traumatized kids, puts it thusly: “regulate, then relate, then reason”.

If you feel like you need the support of a mental health professional, remember that you’re not alone! If you have any questions, please contact us, we’re here to help!

By Sharon Burris-Brown, LICSW, NBC-HWC

Resources

- https://www.mntraumaproject.org

- The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog. Perry, Bruce, Szalavitz, Maia. Basic Books. (2017).

- The Trauma Center at JFI. www.traumacenter.org

Articles

- https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/about.html

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327784916_Parent-Child_Attachment_and_Children’s_Experience_and_Regulation_of_Emotion_A_Meta-Analytic_Review

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5859128/